By Michael W Edghill

CJ Contributor

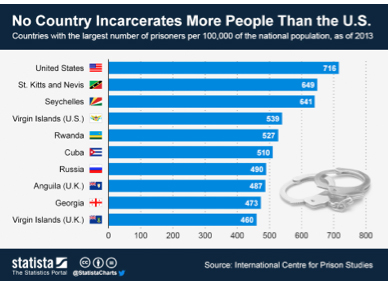

Every now and again, a report or statistic comes along that presents something genuinely surprising. A few weeks ago, that statistic came by way of a graphic shared through social media. The graphic showed the nations with the highest incarceration rate globally.

This graphic was an illustration of a study by Britain’s International Centre for Prison Studies. What it revealed was that, while the United States topped the list, the incarceration rate amongst Caribbean nations was one of the highest in the world.

If you absent the US, 10 of the top 50 nations on this list were Caribbean states. That total rises to 11 if you include Cuba, although it is more appropriate to exclude Cuba due to the fact that political prisoners make up a known portion of the incarcerated in that island. These statistics, while not shocking if one takes the time to think about the known crime troubles in many of these nations, still cause one to stop and reflect on why so many are incarcerated throughout the region. And is this a problem that needs to be addressed?

The cause of so many being detained regionally is rooted in three main issues. First, crime has become a serious regional issue since the 1980s. The second issue is that, as a result of this crime surge, the justice systems of the region have been overwhelmed and have become backlogged when trying to adjudicate criminal matters. The third issue is that many Caribbean states have instituted US-style reforms to the criminal justice system in an attempt to combat the crime problem. In short, when you implement the same strategies, you end up with the same results.

As it regards the regional crime epidemic, it is news to very few that drug trafficking has become the single gravest plague on citizen security throughout the Caribbean.

The wave of cocaine smuggling that began in the 1980’s has ebbed and flowed over time as transnational drug trafficking cartels and their affiliates have created smuggling routes, fought wars with governments to maintain their smuggling routes, and then moved their operations to other locations and shipment points.

As the Mexican government has engaged in combating the drug cartels operating within their territory and the United States has zeroed in on Central American nations as the major transit points of concern over the past six-plus years, drug trafficking has again started to migrate towards Caribbean transit points.

In his April 2013 article in Time, Tim Rogers was writing on the efforts to eradicate drug trafficking from Central America. Rogers quotes Ethan Nadelmann, executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance. Nadelmann was speaking about comments made by William R Brownfield, United States Assistant Secretary of State for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, when he suggested that the more the drug war succeeds in Central America, the more it will create problems for the Caribbean.

What perhaps separates this renewed escalation in the Caribbean drug trade from earlier incarnations of decades ago is the degree to which trafficking has become proficient in terms of the business model. Daurius Figueira, lecturer of Sociology at the University of the West Indies St Augustine, referred to it as a “Caribbean division of labour.”

He elaborated on the modern drug trafficking business and described it as follows. “Jamaican producers and traffickers have forged operational links with Haitian operators where Haitian labour is used on Jamaican ganja farms, the product is moved to Haiti and exchanged for a range of commodities including arms and ammunition and from Haiti the product is trafficked to the US.”

This description indicates a highly sophisticated multi-national logistics system that, like any profitable enterprise, stands to grow in size when people can profit at all points in the supply chain. If one ever wondered why crime, specifically drug-related crime, grew so rapidly and continues to plague the Caribbean region, the prior points are illustrative of the nature of the problem and just how deep it runs.

As a result of this problem, the justice systems throughout the region are operating well beyond their capacity and it is the citizens that suffer because of it. The negative effects of the overwhelmed justice system tend to trickle down and can have long term impact. An examination of the UN Caribbean Human Development Report for 2012 reveals a few things. The fifth chapter, focusing on the criminal justice system, highlights the problems of a system that has criminal charges to adjudicate but not the resources necessary to handle the volume of cases brought before it.

The result is a system that detains a sizeable number of citizens in pre-trial or remand conditions as they await trial. The sheer number of people that require housing in government detention facilities not only taxes the finances of government but, in many cases, necessitates undesirable conditions. Among these undesirable conditions are the housing of juveniles with adult detainees as well as the detention of juveniles in non-criminal matters with juveniles who have committed serious offences. The 2012 report states the results of this in clear terms:

“Because it is a long truism of criminology that one of the most potent causes of delinquency is exposure to delinquent peers, any strategy that houses minor offenders together with serious offenders is likely to increase crime.”

Additionally, the overwhelmed system often leads to procedural errors in which criminals get released as well as a general feeling of ‘justice delayed’ which reduces citizen confidence in the justice system and in the government’s ability to handle the crime problem.

The 2012 report highlighted many more negative consequences from the overburdened justice systems in the region and makes it abundantly clear that this is not only a procedural problem, but a problem that breeds more crime.

What also can be seen as a contributing factor to the overwhelming incarceration figures in the Caribbean region is the effect of US-style criminal justice reforms. Many of these reforms have been a result of United States influence by the way of the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI). Open Society Foundations published a report in 2009 that stated that the US-led “war on drugs” has “led to an increase in the number of persons imprisoned on drug-related charges.

Drug war policies adopted in the Caribbean with US financial support, for example, led to the imprisonment of a large number of people who use drugs or associated with the drug trade, resulting in prisons filled beyond capacity.”

This same report highlighted the fact that the main foreign policy objective in the region has been combating drug trafficking and therefore a substantial amount of foreign aid, as much as 50 percent, has been directed towards that goal.

“Where the United States, through military and financial support, has shaped national governments’ counter-narcotics strategies, drug control has focused primarily on supply reduction through eradication of coca leaf plantations; the detention and punishment of drug traffickers; and the interception of drug shipments in campaigns such as Plan Colombia and the more recent Merida Initiative.”

The report of The Open Society Foundations is not the only voice that speaks to this fact. In June of 2013, Michael Shifter, President of the Inter-American Dialogue, testified before the House Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere concerning CBSI.

Speaking about the effectiveness of current US policy in the region, Shifter said the results prompted “serious questions about the focus and scale of US assistance and Washington’s overall approach”. He pointed to a Government Accountability Office report from March of 2013 that indicated that “over three-quarters of the money committed or disbursed through CBSI between 2010 and 2012” was directed towards either international narcotics control and law enforcement or towards foreign military financing.

The fact of the matter is that the evidence suggests that the zero-tolerance, militarized ‘war on drugs’ that the United States employs as policy and encourages others to adopt is taking a substantial toll on the Caribbean.

Alternatives to the current policies utilized as a part of the “war on drugs” do exist, though supporters of these alternatives are often derided as “soft on crime”. Current policies measure effectiveness in the number of drug related offenders incarcerated.

The success of alternative policies; whether it be alternative sentencing, decriminalization of small-scale drug charges, or some other idea; can only be measured by crime reduction over time. A sliver of hope for those who point to alternatives to the current drug policies can be found in the reporting of Damien Cave who, in a New York Times piece from August 17, wrote of Jamaica’s efforts to find new, more effective ways to combat crime.

“Since 2009” Cave writes, “no other country has received more American aid from the $203 million Caribbean Basin Security Initiative, yet relatively little of it has been directed toward the muscular, militarized efforts financed elsewhere as part of the war on drugs.”

Instead, the emphasis has been on “community policing, violence reduction, and combating corruption”. The results are that Jamaica has seen a 40 percent reduction in the murder rate since 2009 and is now hailed as one of the least corrupt nations in the Americas as opposed to one of the most corrupt.

This small sample is evidence that alternatives to incarceration can have a meaningful and lasting effect. Instead of continuing to pour money from CBSI into the growing militarization of the “war on drugs” and into punitive incarceration instead of corrective rehabilitation, Caribbean states should take a long look at alternative means of tackling the drug-crime issue within their territories. Maintaining the status quo is unacceptable.

Instead of merely medicating the disease, examining new ways of treating the cause is necessary in order to win the future of the Caribbean. And the future is the youth of the region. “Preventative programs to tackle youth crime and general unemployment must be instituted and supported by Caribbean governments and their international partners”, writes Kevin Edmonds, blogger for the North American Congress on Latin America.

In his article on the militarization of the drug trade in the Caribbean from February of 2013, he concludes that “Like anywhere else, it is the overall lack of opportunity which creates foot soldiers for the drug trade.”

Therefore, Caribbean governments should direct their own resources and the resources made available to them from foreign aid at the cause of the disease. Work to create investment opportunities. Work to create accountable government that provides confidence for foreign investors to create jobs. Focus money towards aiding the overwhelmed judicial system so that its detention facilities do not become a recruiting ground for future drug kingpins. In short, escalating the “war on drugs” in the Caribbean can only neutralize the drug trade.

While governments have an unending revenue source to buy guns, tanks, drones, etc. by way of taxes, multinational drug traffickers too have an unending revenue source for guns, armored vehicles, and go-fast boats by way of purchasers in the drug market. In the long run, the only way to truly gain the upper hand is to provide viable alternatives for those in society who are looking for a way out of their impoverished situation.

Detaining a significant portion of those people for a lengthy period of time does very little to solve that problem. Instead, it helps perpetuate a cycle whereby poor youth with few options turn to small-time drug sales to earn income. They are caught, detained and incarcerated with more hardened criminals. This in turn increases the likelihood of recidivism.

Once released, they have difficulty finding work, especially with their record, so they turn back to criminal drug activity. And the cycle continues. While not suggesting that hardened criminals and drug traffickers don’t deserve to have the full weight of the law brought to bear on them, it is advisable for Caribbean governments to evaluate alternatives to incarceration for first-time, small time, and youth offenders. The evidence suggests that it may be the only way to chart a markedly different path for the future of the Caribbean.

Michael W Edghill, a Caribbean Journal contributor, teaches courses in US Government & in Latin America & the Caribbean in Fort Worth, Texas. He has been published by the Yale Journal of International Affairs, Diplomatic Courier, the Trinidad Guardian, and others.

Follow Michael Edghill on Twitter: @MichaelWEdghill

The Perfect Jamaican Jerk Recipe