Author Matthew Parker on Sugar and the Rise and Fall of the British West Indies

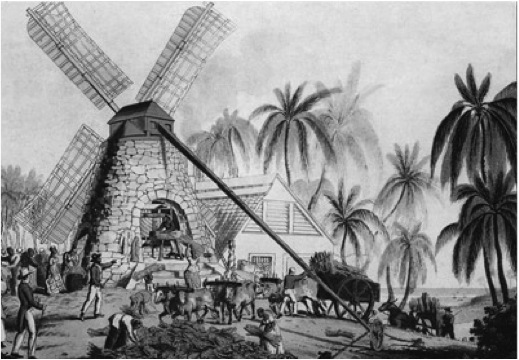

Above: a sugar mill in the 17th century (Photo: www.matthewparker.co.uk)

By Alexander Britell

The Caribbean was built largely on the success of its sugar crop — and the story of the success and decline of “white gold,” and the wide-ranging impact it had not just on the West Indies, but America, as well, is the subject of Matthew Parker’s book, The Sugar Barons. Parker describes more than two hundred years of history in the British West Indies — from James Drax, who introduced sugar to Barbados (and whose direct descendant is an MP in England) to how Britain’s focus on the West Indies may have cost it the American colonies. Caribbean Journal talked to Parker about Barbados, his research in the Caribbean and how the sugar revolution changed England.

What made you decide to write The Sugar Barons?

I’m English, but I lived in Barbados for about four or five years in the 1980s, and became very interested as a teenager and obviously loved it. I thought that it was a very strange place, and got to travel around the island a little bit, and really have been wanting to do an accessible history of a few of the stories from the region for a very long time. For me, it’s the most fascinating history of anywhere in the world — it’s so influential and so key to the way that Britain developed and the way the US developed and the islands of course. It’s a shocking, extraordinary and often exciting history, and I think a lot of people go there and sit on the beach and don’t realize that they’re in Rodney Bay [in St Lucia] and this was somewhere that — Philadelphia was abandoned during the American revolution in order to conquer St Lucia. The whole thing is so counterintuitive to us now — how important the islands were — but the influence they’ve had on world history is quite extraordinary and I really want more people to know about that.

Talk about what sugar meant to the growth of the West Indies.

I think the moment when sugar was planted in Barbados in the 1640s completely changed it. If Barbados had grown cotton, or a little bit of tobacco, it’s impossible to overestimate the difference that would have made, considering how the plantation system in the Anglo-Americas was born in Barbados and created there — incredibly quickly and exported all around the Caribbean to South Carolina, started New England going in the 1640s and 1650s. I think that’s before you look at the influence on diet — and the creation of these other rather useless tropical commodities. Along with sugar, you’ve got tobacco, coffee and tea, all of which are pretty useless, if not actively bad for you, and created this sort of consumer mentality that made people spend five cents of their income on sugar — and they were happy putting in their hours at the factory for the luxury. And that’s before you start talking about slavery.

How did the “sugar revolution” change England?

For quite a long period of modern English history — we’re really talking about from 1650 through the 1930s, it created this whole community of entrepreneurs that was prepared to get on ships and take huge risks for huge rewards, and really created Britain’s strength for many years as the leading commercial power– rather than the sort you had in the autocratic regimes in Europe at the time. A lot of the colonies were funded and founded for the purpose of sugar — so it created the mercantile empire of the early English empire period, and, of course, it opened the fissures between London and the likes of Newport and Boston, because the West Indies was just so much more important to the empire than the North American colonies, and that led directly to the war of independence. That’s the arc, really — from sort of creating and fueling the English empire, and obviously the focus changes when the catastrophic decline of sugar islands occurs at the end of the 18th century.

Did anything surprise you in your research?

Yes. Virtually everything — one of the great pleasures of doing this sort of book and spending the sort of time that I did on it — something like five years — is a lot of travel and a lot of going to see some really quite tucked away and small archives. I remember being in Newport at the Newport Historical Society, and they’ve got this amazing collection of letters from slave-owning people who lived in Newport and Antigua, and seeing the actual paper, and the letters that came in from the islands, and the lists of who died and what they died of, it’s absolutely fascinating. The same thing happened in Spanish Town [in Jamaica] when I went to the archives to look at the Beckfords [one of the sugar-owning families covered in the book] and the inventories of their possessions and just page after page of people’s names and something like 2,500 people. One of the tinges that I didn’t know as much about as probably some of the readers in North America, and certainly the British-reading public isn’t aware of , was how interlinked the Atlantic British Empire was — how interdependent they were, right up until the revolution. And when the revolution occurred, and they were broke, it was a complete disaster for the West Indies. Of the North American colonies, half of the trips coming out of Boston were involved in the West Indian trade.

Was there one island that suffered the most from the decline of sugar?

That’s a huge question. I think some islands are in better situations than others — I think on the whole, my experience is really with the West Indian diaspora in London more than anywhere else, and I think it’s easy to forget that a lot more West Indian-originated people live outside the West Indies. There’s a huge world population of West Indians. One thing that really shocked me as I was doing a magazine article for the BBC’s genealogy magazine, was that there were so many people — and this is something I’ve discovered — there’s hardly anyone who hasn’t someone in their family tree who had a West Indian adventure, whether you’re in any part of the UK. And, I know this to be true, that includes a lot of persons in the US as well. It’s really a part of a lot of people’s family stories here in the UK.

Do you have a favorite character or family from the book?

Funnily enough, we had a launch party when the book came out in the Spring, and I managed to get along with a guy called Christopher Codrington, who is the direct descendant to one of the three big families that I wrote about. And he was such a charming bloke in a very sort of English way, and he didn’t seem to mind that I’d accused his ancestor of the most heinous crimes! But they were a really fascinating family, because they were highly intelligent, highly educated and, first of all, meant well. They really wanted to create a working society, and they went out with the best of intentions to try and get a sort of white immigration, so they wouldn’t have to use slaves. But they succumbed to the heat and the rum, the power and the money. I thought they were an absolutely fascinating family. The other person I invited to the party was Richard Drax, who is a Member of Parliament here in Dorset for the Conservative Party, and he, being in the public eye, wasn’t so keen to be associated with his family history. His family is still in Barbados, where it all began — it’s still in the hands of the same family. He didn’t want to come to the launch party, but has been very charming.

What was the research like for this book?

Well it was very different. In terms of archives — and it depends on what you call research — I was able to find virtually 70 percent of the archive material I used here in the UK, or in Rhode Island, in Providence and Newport, and the archives there. And there were some bits and pieces that I found in the West Indies, but most of all, it was just talking to people. I’ve been there off and on, but not on my own — going to places I wouldn’t have done that were off the beaten track. That was an amazing experience. It’s so different where I am here in rainy East London, going out there on a boat, and how strange it must have been for them — how much more strange. But it’s still a really interesting, fascinating, strange, magical place.

Find out more about Matthew Parker at www.matthewparker.co.uk.